(Part 2) Sandwich Patent War, Math Formula, & the State of the 21st Century Consumer Market

Calculating every possible PB&J combo, copyright battle over the shape of a sandwich, and Economics 101 (market concentration / fragmentation, substitutes / complements)

Previous Publication: (Part 1) 20th Century American History through the lens of PB&J Sandwiches

You truly can’t get more American than a classic PB&J sandwich on white bread.

In Part I we saw that what appears to be a seemingly simple concept holds a special place in American history. The fact that we have phrases such as “greatest thing since sliced bread” and “as American as PB&J sandwiches” speak to their ingenuity and impact on American culture and society. However, we’re not done…

Trademarking the taste of nostalgia?

At the end of 2022, Smuckers entered into a trademark battle with Gallant Tiger, claiming that its use of the round crustless design is copyright infringement. Gallant Tiger is a small business based out of Minnesota that sells gourmet, “adult” versions of round, crustless, peanut butter sandwiches in various flavors. One can see why Smuckers feels threatened.

Smuckers sent a “cease and desist” letter to Gallant ordering it to halt all manufacturing and selling, claiming,

“We have no issue with others in the marketplace selling prepackaged PB&J sandwiches, but Gallant Tiger’s use of the identical round crustless design and images of a round crustless sandwich with a bite taken out creates a likelihood of consumer confusion and causes harm to our goodwill in our Trademark…we are not intending to restrict competition, rather…avoid instances of deliberate copycat.” (Star Tribune).

In 2022 alone, Uncrustables sales reached $511 million and Smuckers projects that sales will surpass $1 billion by 2026 (one would think that a small mom-and-pop business would be the least of their worries). Gallant’s response was quite direct and telling, and they made it known they have no intention of complying with Smucker’s threats:

“From a traditional trademark perspective, a customer would not mistake the two, because our price point is different, our packaging is different, and our quality of ingredients is also significantly different. In fact, we’re twice as expensive as the market leader. So, if somebody saw us in store side by side, why wouldn’t you just go with their product”.

Does Smuckers complaint hold any water or are they simply threatened by a newer, better, and higher quality alternative? And is it even possible to trademark the taste of nostalgia?

From a branding perspective this is both a positive and negative for Gallants. Here’s why:

(+): Gallant is a new kid on the block and Smuckers, the behemoth, had clearly noticed them. The fact that they feel threatened is a sign Gallant is moving in the right direction in terms of its branding, product development, and advertising. This places Gallant it on the same stage as Smuckers. Smuckers could have inadvertently pushed consumers towards Gallant because now they are aware of yet another options to choose from.

(-): In the U.S. there are trademarking laws that could potentially land Gallant in hot water if courts rule copyright infringement.

Trademarks, patents, and copyright laws provide legal protection for brands, ideas, and methods. These are often used interchangeably but they in fact refer to three different types of protections:

Patenting the Shape of a Sandwich

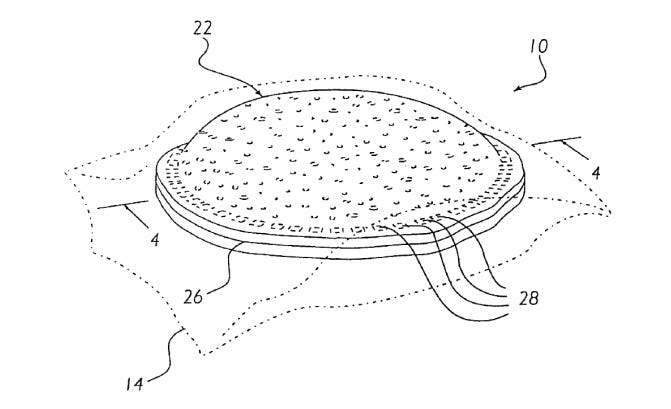

Smuckers first patented the sealed crustless sandwich in 1999 (drawing below). However, many have criticized the absurdity of patenting something as commonplace as a sandwich preparation method. Finally in 2005, a federal court ruled that the sealed, round, crustless PB&J was “was not novel or non-obvious enough to merit the award of a patent.

Smuckers has been selling its Uncrustables without a patent since then, which is why it has resorted to going after competitors directly. Gallant Tiger is by no means the first, and likely not the last, target of Smucker’s cease and desist letters.

Anatomy of a PBJ Sandwich

Simple sandwich, simple way to make it? Yes and no. The process is simple, yes, but the ingredient selection process not so much.

PB + J + Bread = PBJ Sandwich

The process starts with choosing the type of “butter”, be it peanut, almond, pistachio, sunflower, cashew, hazelnut, list goes on. You also have to settle on crunchy or smooth.

Then you have to choose the type of jam and based on the consistency, you might opt for jelly or marmalade instead. You also have to choose the type of fruit for your jelly - apricot, blueberry, raspberry etc.

Then comes the bread. Gluten / gluten-free aside, there are so many different options you could opt for - white, sourdough, multigrain, pumpernickel, raisin, baguette, Hawaiian rolls etc. Heck, you could even make a PBJ sandwich on naan or challah.

You’re also not constrained to a square sandwich - you can recreate the circular Smucker’s Uncrustables (early 2000’s nostalgia), cut it into triangles, or if you really want to get fancy, make PBJ hors d'oeuvres in the shape of mini pinwheels. Sky is truly the limit here.

Finally, all of these components come together to make your one-and-only, truly unique PBJ sandwich. Consider yourself an engineer - assembling parts and creating an edible masterpiece.

Stats 101 on Finding the Perfect PB&J Combo

Let’s break down the equation that makes up a PBJ sandwich.

In statistics, a combination represents a selection of objects in which the order that they are selected does not matter. In order words, in how many ways can you combine the different types of bread, jams, and peanut butter to create a sandwich in which you select one of each?

So how many options are there?

PB = There are ~ 87 different peanut butter producers in the U.S.

J = Will estimate that there are ~100 different jelly / jam / marmalade options

Bread = There are ~100 different bread varieties

(PB)*(J)*(Bread) = (87)*(100)*(100) = 870,000 different PBJ options

This means that there are approximately 870,000 ways to combine the different types of PB, J, and Bread to create a PB&J sandwich.

*Caveat*

One huge caveat that is worth noting. This is more an illustration on the plethora of options rather than a “scientific” calculation. So while we should take this with a grain of salt there are many learnings we can gain as to the state of the three respective markets: peanut butter, jam, and bread.

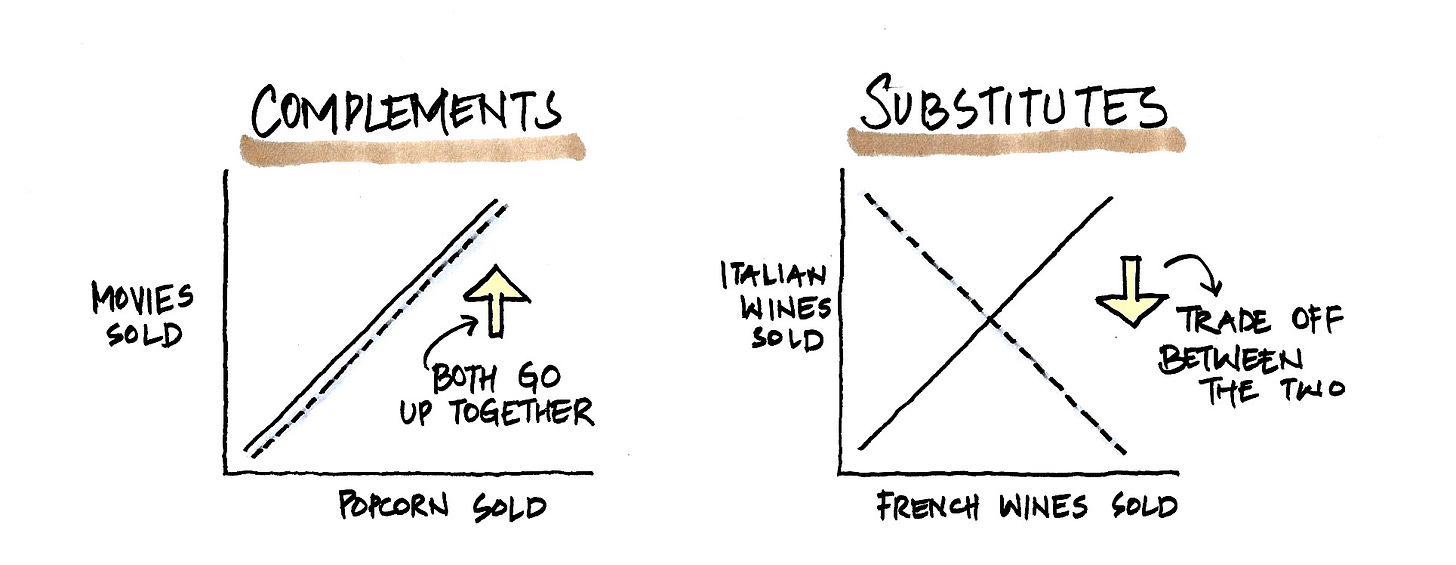

Complements vs. Substitutes

Many goods have their consumption tied to the prices and / or consumption of other goods. For example, it’s unlikely that someone would buy a Coca Cola and a Pepsi at the same time, but it is likely that someone would buy a Coca Cola and chips to go with it. This makes the former substitutes and the latter complements. Let me explain:

Substitutes: A product or service that DECREASES a consumer’s desire and need for an alternate product or service (consumed interchangeably, considered replacements of one another)

Examples: Coca Cola & Pepsi, Peanut Butter & Almond Butter

Complements: A product or service that INCREASES a consumer’s desire for another product or service (consumed together)

Examples: Peanut Butter & Jelly, Printer & Ink, Razor & Blade

In order words, peanut butter, jam, and bread are complementary markets - demand in one market positively impacts the demand in the other two.

One Sandwich, Nine Different Ways

If you really want to push the limits on all the different PB&J combos you can create one sandwich with nine different flavor combinations - who says American consumers are not inventive?!

We all got quite creative with our time during the COVID lockdowns. This definitely changes our math a bit!

Characteristics of a Fragmented Consumer Goods Market:

Examples: (most) packaged consumer goods, frozen foods, beauty products

Market with low barriers to entry means that you are likely to see many alternatives and therefore likely to be highly fragmented

Ease of production: stable consumer foods have a relatively long shelf life and don’t need to be refrigerated (cheaper to produce, transport, and display on shelves)

It is easy to create a new alternative by mixing and matching components such as origin / sourcing of ingredients (type of nuts, using misshapen fruits), packaging, pricing, flavoring (chocolate, honey), consistency (jam, jelly, marmalade), nutritional content (no high fructose corn syrup or palm oil), use case (food, drink, smoothie, salad), and distribution channel (DTC, supermarket, farmer’s market)

Strong focus on engaging consumers through brand campaigns and promotions (why a consumer should purchase from Company A vs. B)

The customer base is highly diverse - there are market leaders across the nut butter and jelly categories but no singular brand can cater to all tastes and preferences which is why so many options exist

Fast-followers approach - waits for a competitor to successfully innovate and moves fast to imitate the approach

Characteristics of a Concentrated Consumer Goods Market:

Many of the elements that make up a concentrated market are the exact opposite of what make up a fragmented market. Concentration is measured to the extent that one or a few players control an outsized percentage of market share. Industries tend to consolidate / become more concentrated as they mature.

Examples: airlines, pharmaceuticals, soda

Barriers to entry for new players are very high due to high defensibility. There are 3 types of barriers: natural (startup costs are high and not many have the resources), imposed (created by current competitors to limit new entrants), and policy-based (this includes health and safety regulations, licensing / patent requirements, and other restrictions)

Customer preferences have converged / a few players are able to meet customers’ needs, preferences, and tastes

Over time, smaller players that cannot keep up inevitably exit the market, creating even more concentration among the current players

First-movers approach - product development focused on being first to innovate and improve product quality

A prime example of this is Coca Cola & Pepsi. They are essentially a duopoly. Collectively, they control 71% of the U.S. soft drink market. They don’t compete on price but instead on taste and brand image. Competing on price would be a losing game for both as their margins would erode in a pricing war. Another example is Google which dominates over 90% of the search engine market.

—> High market share tends to correlate with high brand equity - the more customers value, recognize, and trust a brand the more they are likely to be loyal to it.

Can a Market Have Many Options Yet be Highly Concentrated Among a Few Brands?

These are not really binary terms, meaning it’s not an either or but more of a spectrum. Often times a market is somewhere in between highly concentrated and highly fragmented. Fragmented industries are usually in their growth stage while concentrated / consolidated industries are typically more mature and established markets. Some industries become naturally concentrated while others as a result of policies, regulations, and government funding efforts.

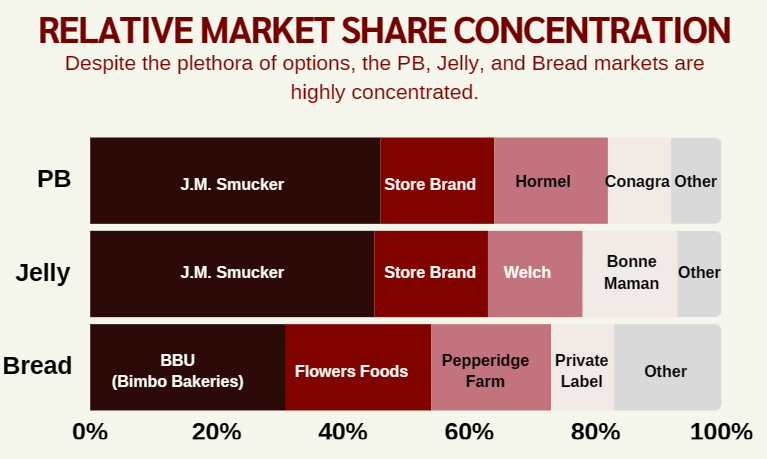

While it may seem like the peanut butter, jam, and bread markets are fragmented given the seemingly large number of options they are in fact highly concentrated. Just take a look at the below chart which outlines concentration across the top 4 brands.

Nonetheless, while the top brands control majority of the PB, J, and bread markets, there is a long tail of smaller players that cater to various consumer tastes and preferences which is where the sub-market fragmentation sits.

—> In short, a market can be fragmented as a whole but have sub-market concentration and similarly be concentrated as a whole but have sub-market fragmentation, as is the case with PB, Jelly, and Bread.

Industry Concentration & Pricing Power

Monopolies are not just reserved for board games. They are in fact more widespread than we often (like to) think. However, just because a brand has a monopoly on the market DOES NOT mean that it has strong pricing power (aka ability to set and determine price). How can this be?

Take the peanut butter market. Top four brands make up 92% of the market yet there are 100s of peanut butter options.

This is because the barriers to entry are low - it is easy to make peanut butter at home and it is not a highly regulated market (you can even buy specialty peanut butter on Etsy…)

Take a look at the below axis of Quality x Price. Most brands are along the diagonal line (with a few exceptions). Most avoid the high quality x low price or low quality x low price corners for three main reasons:

Price signals quality (to an extent) and if a product is too cheap consumers might associate it with low-quality (the assumptions being that high quality ingredients are more expensive and garner a higher price)

Given that there are budget options such as Smuckers that are often full of sugar and hydrogenated oils (aka not a 100% peanut butter product) consumers are likely to assume that any product with a similar price as Smuckers is of the same quality

Because there are so many options no one would knowingly choose a low quality and low-priced peanut butter

This wraps up our discussion of the American classic that is the PB&J sandwich!